In my last blog post, I wrote about what I’ve learned about International Development in my two years of service as a Peace Corps Volunteer. In this post, I’ll try to make some observations about what I’ve learned in the same time about myself and the world that we live in. In no particular order, here are my thoughts:

1. The world is a big, beautiful place. As I have observed often in this blog, Kyrgyzstan is spectacularly beautiful—everywhere. Here in Naryn, we are blessed to have mountains right in town—they form the southerly boundary of Naryn. And they reveal a different aspect of beauty each day—indeed, almost each hour. Snow falls and melts, clouds roll in, the sun dapples the slopes or bathes them in an ethereal light. I will miss the mountains. And the lakes. The forests. The flowers.

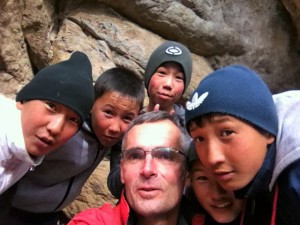

And, of course, the people. People are beautiful, all over the world. Here in Kygyzstan, there are the ak sekals (literally, white beards)–old men—with their whispy beards, their kalpaks, and their hard eyes.  And the old women—stooped, bow-legged, many with large laps for holding multiple grandchildren. There are the children, with their bright, dancing eyes, their rosy cheeks, and their wild abandon. The men, with their swagger and their quick laughs, and the women, with their beautiful, long hair and their shrewd eyes. Each face reflects a life, an invitation to enter into another world.

And the old women—stooped, bow-legged, many with large laps for holding multiple grandchildren. There are the children, with their bright, dancing eyes, their rosy cheeks, and their wild abandon. The men, with their swagger and their quick laughs, and the women, with their beautiful, long hair and their shrewd eyes. Each face reflects a life, an invitation to enter into another world.

And people have beautiful hearts. When I ask my students about their hopes and dreams, helping their families and their communities are always near the top of their lists. And it’s not just talk: families depend on every member’s contributions. One of my students has worked in Turkey each summer for the last three years and brings home several thousand dollars each year for her family. She is a primary bread-winner for the family. The Kyrgyz have a wonderful practice of toasting one another on special occasions, and the toasts are often amazingly thoughful and heartfelt. A sincere Kygyz toast from a good friend is better than any jewel or gadget.

2. It’s also small. People are similar all over the world. They want the same things: friends and family; hope for the future; an opportunity to be useful, to contribute to their communities; to be safe and free from coercion. Before I came to Kyrgyzstan, I read about its economy and low per-capita income, and I expected a very poor country. But Kyrgyzstan doesn’t feel poor. Almost everyone has enough food to eat, clothes to wear and a warm, dry place to sleep. And people are happy. The grimness that I associate with the Russians is not in evidence here; instead, people are quick to smile and they love a good joke.

We make much of religious differences, but, really, most of the world’s religions are more similar than they are different. All religions seem to me to focus on how to contribute to a community and how to live a good, satisfying life. My muslim neighbors here in Kygyzstan have values very similar to my christian neighbors in America. They care for their families and their neighbors; they try to be honest and helpful; they pray to God for strength, for peace, for help and in thanks.

3. But it’s not fair. Liberal guilt is one of the main reasons I signed up for Peace Corps. We have so much in America: so much money and opportunity. Much more than people in most of the world. I had thought that people in other parts of the world must resent Americans for consuming such a huge share of the world’s resources, but, at least in Kygyzstan, they don’t. There is inequality everywhere, and, no matter where in the world you are, there is someone whose life looks more attractive. That’s true in America, as it is in Kyrgyzstan. And I think everyone, all over the world, accepts unfairness as a part of life.

That doesn’t mean that unfairness is right, or that it can’t be changed. But one thing that I have learned living in Kyrgyzstan is that it’s much easier to address unfairness in one’s own culture than to address unfairness in another culture. We are all mistrustful of others’ attempts to tell us how to live our lives. And Americans seem especially driven to tell people in other cultures how they should be living. We have plenty of unfairness in America, and I plan to spend more time in the future working to reduce the inequality that exists in America. I believe that, as humans, we each need to work to make our world a better place. For me, that means working within the culture I know best to make it more fair, kind, open and inclusive.

4.  I’m not dead yet. I’m 57 years old. Catherine, my wife, and I have raised three children to adulthood. I practiced law with a wonderful law firm for 27 years. When I joined the Peace Corps, I didn’t feel dead, but I did feel deadened, stuck in a rut that I had been treading for as long as I could remember. Part of being an adult, part of being a good parent, is being willing to tread that rut for the benefit of others, to build a community, to give our children a stable, nurturing home. When I became a parent, I felt the yoke of those obligations strongly. I didn’t hate it—didn’t even dislike it—but it weighed heavy on my shoulders. In time, I got used to it–it became my life—I life I grew to cherish. . But it was a life largely defined by what I could give to other people. That creates a complexity and a richness that I miss and plan to return to, but it also led me to lose sight of myself, at least to some extent.

I’m not dead yet. I’m 57 years old. Catherine, my wife, and I have raised three children to adulthood. I practiced law with a wonderful law firm for 27 years. When I joined the Peace Corps, I didn’t feel dead, but I did feel deadened, stuck in a rut that I had been treading for as long as I could remember. Part of being an adult, part of being a good parent, is being willing to tread that rut for the benefit of others, to build a community, to give our children a stable, nurturing home. When I became a parent, I felt the yoke of those obligations strongly. I didn’t hate it—didn’t even dislike it—but it weighed heavy on my shoulders. In time, I got used to it–it became my life—I life I grew to cherish. . But it was a life largely defined by what I could give to other people. That creates a complexity and a richness that I miss and plan to return to, but it also led me to lose sight of myself, at least to some extent.

Serving here in Kygyzstan has given me the opportunity to see myself more clearly. Not as a husband, a father, a citizen, or an attorney, but just as an individual. Partly, it’s because that’s where many of my Peace Corps colleagues are in life. Most of them are in their twenties, like Catherine and my kids, trying to figure out where they belong, who they are, and what they’ll become. It’s tough, serious, important work. And talking with them and spending time with them has given me some space and time to ask some of those questions of myself, questions that I haven’t had much time to revisit since I was in my twenties.

I like people. I like adventure. I like helping people. I like to laugh and have fun. None of those things is a revelation to me, but they’ve become clearer while I’ve served in the Peace Corps, and I hope and expect that that clarity will help direct my future.

5. There’s no place like home. I have enjoyed almost every minute of the two-plus years that I’ve lived in Kyrgyzstan. Every day has been an adventure. I’ve made many good friends and been to some amazing, beautiful places. But I want to go home. Catherine and I have built a life together, a life that I sorely miss. Our kids, our families, our friends, our neighbors, our home, my colleagues and clients—I miss them all, every day.

I now realize clearly what a charmed and magical life I lived in America. It was easy and comfortable, filled with interesting conversation, delicious food and drink, and regular visits with dear family and friends. And, so, it was filled with love. Yes, I love new friends here. But back in Minnesota, I have friends who I have laughed with for fifty years. Catherine and I share memories from over 30 years of marriage, of challenges, great joys, shared experience. Each of our children is a unique, fascinating individual, with skills, talents and experience to share. Life is very, very good—almost everywhere in the world. But my home is in Minnesota, and I am delighted to look forward to my impending return there.

As I have mentioned before, Kyrgyzstan is a very, very beautiful country. But its greatest beauty—and its greatest strength—is its people. I have been fortunate to meet, and to learn from, many wonderful Kyrgyz people in the two-plus years that I have served here, and I want to thank you all for helping me and for being my friends.

As I have mentioned before, Kyrgyzstan is a very, very beautiful country. But its greatest beauty—and its greatest strength—is its people. I have been fortunate to meet, and to learn from, many wonderful Kyrgyz people in the two-plus years that I have served here, and I want to thank you all for helping me and for being my friends.

Well, my service here in Kyrgyzstan is winding down. In less than two months I’ll be closing out my Peace Corps service and going back to the USA. So it seems like a good time to think about what I’ve learned by serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Kyrgyzstan. And I want to blog about it in two parts: What I’ve learned about Kyrgyzstan and about international development, and what I’ve learned about myself. This post will be about the former, and my next about the latter.

Well, my service here in Kyrgyzstan is winding down. In less than two months I’ll be closing out my Peace Corps service and going back to the USA. So it seems like a good time to think about what I’ve learned by serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Kyrgyzstan. And I want to blog about it in two parts: What I’ve learned about Kyrgyzstan and about international development, and what I’ve learned about myself. This post will be about the former, and my next about the latter.

Here in Kyrgyzstan, we eat a lot of horsemeat. Next to goat, it’s the go-to protein, and the primo meat for any celebration: weddings, funerals, births, new house, new car. National Geographic has

Here in Kyrgyzstan, we eat a lot of horsemeat. Next to goat, it’s the go-to protein, and the primo meat for any celebration: weddings, funerals, births, new house, new car. National Geographic has

Shifting sands, mirages shimmering on the horizon, local people cooking over open fires: before I became a volunteer, these were the sights I associated with the Peace Corps. But you won’t see any of them in Kyrgyzstan. Peace Corps currently operates in 68 countries, and I have been told that only a few of them have “real” winters, where snow and ice cover large parts of the country for weeks at a time. And Kyrgyzstan is one of the coldest. And Naryn is the coldest city in Kyrgyzstan, where the temperature is routinely 15-20 degrees colder than other cities in Kyrgyzstan.

Shifting sands, mirages shimmering on the horizon, local people cooking over open fires: before I became a volunteer, these were the sights I associated with the Peace Corps. But you won’t see any of them in Kyrgyzstan. Peace Corps currently operates in 68 countries, and I have been told that only a few of them have “real” winters, where snow and ice cover large parts of the country for weeks at a time. And Kyrgyzstan is one of the coldest. And Naryn is the coldest city in Kyrgyzstan, where the temperature is routinely 15-20 degrees colder than other cities in Kyrgyzstan.

image by Zuma Press

image by Zuma Press